A Lesser-Known Chapter on Lithuanian Emigration

In the context of the current war on Ukraine, a recent article on the website bernardinai.lt confirms the relevance of refugees and their history. A lesser-known chapter in Lithuanian history was the emigration of Lithuanians at the beginning of World War I.

The first war refugees began leaving Lithuania in the fall of 1914. Most lived close to the front, and were evacuated by the czarist regime. At the time, locals were suspected of aiding the German army, and the first to go were Germans living in the Lithuania. Another group immediately repressed were Jews living in the border zone of the Suvalkai province. They were deported en masse deep into Russian territory.

The main exodus of Lithuanians began in spring/summer of 1915, when the Germans began assaults within Lithuanian territory. This was later named the Great Russian Retreat.

Initially evacuated were Russian administrators, public servants, factories, schools, medical facilities, even psychiatric hospitals with their inmates. The czarist government decided to expel all Jews from Kaunas province. Some of them were deported to Ukraine, as far as Odessa.

Residents were incited to burn their houses, leaving nothing for the enemy to find. In a panic, many Lithuanian farmers began leaving, frightened by stories of German cruelty. Many ethnic groups, including Lithuanians, fled to Russia, in carts and trains or on foot. Others merely moved a few dozen kilometres away from the front lines, thinking that the war would end in a few months.

In all, almost half a million refugees fled Lithuania, including 250,000 Lithuanians, 160,000 Jews, and 50,000 Poles from the Vilnius region. Lithuanian communities began appearing in the Caucasus, Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, and as far away as Vladivostok.

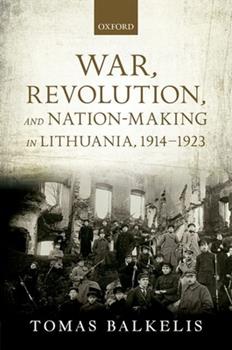

Researchers of Russian history have come to the conclusion that this exodus was one of the factors causing the fall of the Russian czarist empire in February, 1917. Thus Lithuania played a an important role in this event. Many Lithuanians stayed away for four to six years, returning to a new, independent Lithuania, with its totally different political regime. Historian Dr. Tomas Balkelis suggests that the Lithuanians who left were far more active in building their new country than those who stayed behind.

With many new communities of refugees, a need for aid organizations arose, with the principal one being the Lithuanian Association for Aid to Victims of War (Lietuvių draugija nukentėjusiesiems nuo karo šelpti), established in Lithuania in August, 1914. Its role was significant, especially as the Germans took over Kaunas and Vilnius. The association split, with a smaller group staying in Vilnius to help locals, and the majority of intellectuals leaving for Russia. By 1916 there were 250 chapters of the association in Russia, actually receiving funds from the Czarist government, although later the funds were handed over to so-called mutual aid societies.

With many new communities of refugees, a need for aid organizations arose, with the principal one being the Lithuanian Association for Aid to Victims of War (Lietuvių draugija nukentėjusiesiems nuo karo šelpti), established in Lithuania in August, 1914. Its role was significant, especially as the Germans took over Kaunas and Vilnius. The association split, with a smaller group staying in Vilnius to help locals, and the majority of intellectuals leaving for Russia. By 1916 there were 250 chapters of the association in Russia, actually receiving funds from the Czarist government, although later the funds were handed over to so-called mutual aid societies.

The headquarters of the association was in St. Petersbug, providing aid to all Lithuanians in Russia and also helping them maintain their identity and cultural ties to their country, fostering their desire to return to their homeland. Its goal was to unite all Lithuanians and to carry out a census, which was done in 1917. A total of over 200,000 ethnic Lithuanians were registered.

The association encouraged Lithuanian activities and supported Lithuanian newspapers of various political views, such as the national, right wing Voice of Lithuania (“Lietuvių balsas”), and later, the social democratic New Lithuania (“Naujoji Lietuva”). The newspapers enabled the sharing of information and helped people find their relatives and fellow countrymen.

Cultural events became popular, as well as efforts to write down Lithuanian songs, folklore and language. Youth organizations and schools were established to instill Lithuanian values. The Russian revolution inspired the formation of a Lithuanian National Committee, a political organization whose aim was to return all refugees to Lithuania as Lithuanian citizens if the country declared independence.

A Lithuanian seimas or parliament was organized in late May, 1917, in St. Petersburg, to discuss the political standpoint of a new Lithuania after the war. Two schools of thought emerged – one, supported by a majority, maintained that Lithuania must be a neutral state, negotiating its independence with Germany. There were also those who felt that a democratic post-czarist Russia might win the war and Lithuania’s independence would be decided in a new Russian political context.

With the Bolsheviks in power, the refugee aid structure was dismantled. A commission was established to take all of the Lithuanian Association’s funds and assets. All aid was discontinued, but once Russia signed the peace treaty, Lithuanian refugees began returning to their country. At the time it was still under German control, and refugees were processed by Germans screening for invalids, spies and Communists. Once the Lithuanian government was formed, it renewed the policy of bringing home refugees, but the process was very chaotic.

Re-immigration continued until July, 1920, when Lithuania and Soviet Russia signed a peace treaty. A separate department was formed to process returning refugees, who had to provide documentation to prove that they had lived in Lithuania before the war. A humanitarian crisis arose at the borders due to Jews being denied visas. Many refugees were blamed for spreading Bolshevik ideas, and the governing Christian-Democrats were accused of espousing that ideology – as well as spreading contagious diseases.

Re-immigration continued until July, 1920, when Lithuania and Soviet Russia signed a peace treaty. A separate department was formed to process returning refugees, who had to provide documentation to prove that they had lived in Lithuania before the war. A humanitarian crisis arose at the borders due to Jews being denied visas. Many refugees were blamed for spreading Bolshevik ideas, and the governing Christian-Democrats were accused of espousing that ideology – as well as spreading contagious diseases.

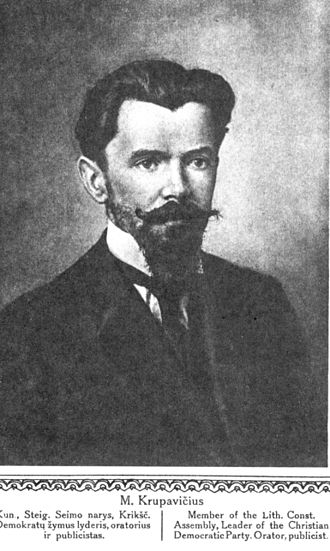

Rev. Mykolas Krupavičius, himself a refugee and a pillar of newly independent Lithuania, wrote that the democratization of Lithuania began not in Lithuania, but in Russia, among the wartime refugees. In his view, their return to Lithuania guaranteed the formation of a democratic nation.