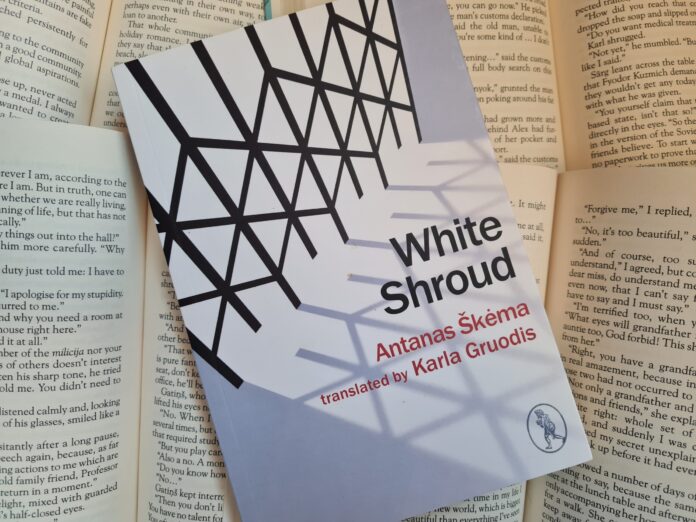

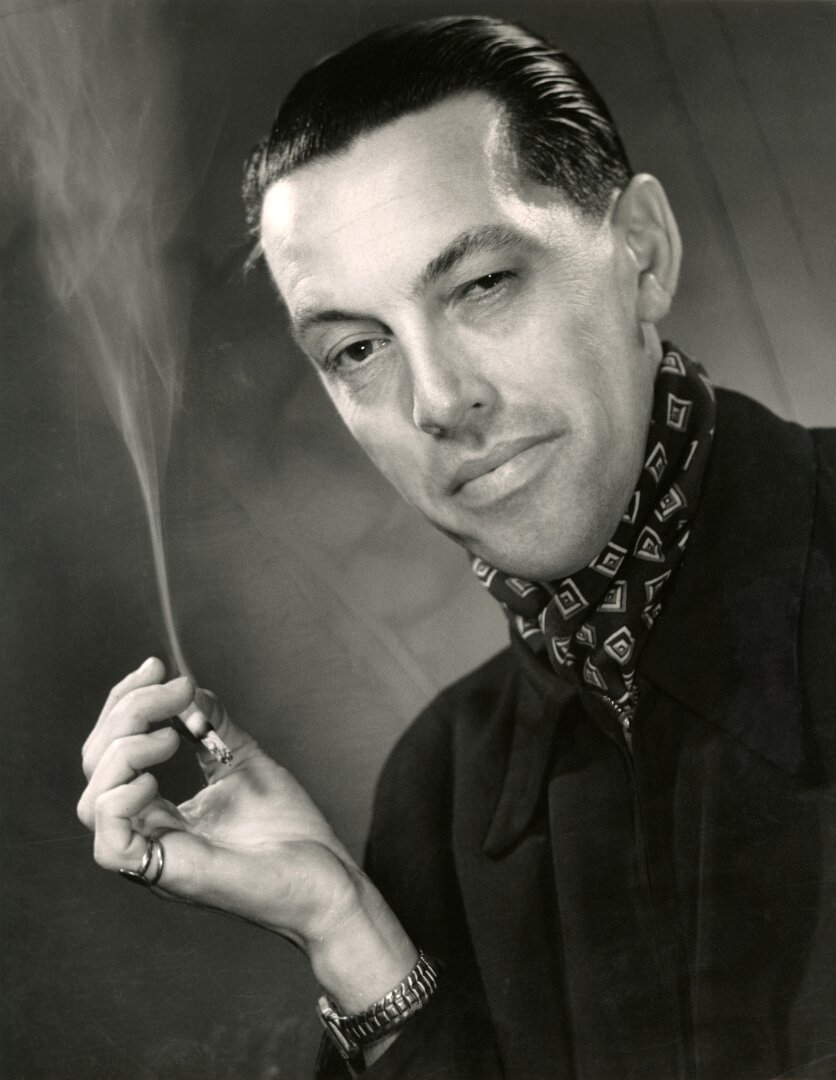

Among many books about immigrants, one that is unique and possibly one of the best is Antanas Škėma’s White Shroud (Balta Drobulė, originally published in 1958, translated by Karla Gruodis and published in English by Vagabond Voices, 2018; transl. by Karla Gruodis). Cultural historian Mikko Toivanen wrote about it for LRT.lt in English quite some time ago, and considered it well worth reading.

Antanas Škėma uses the innovative (for Lithuanian literature) stream of consciousness narrative to great effect, creating entirely his own style. The novel is defined by irony, occasional surrealism, unexpected metaphor, acute stylistic contrasts where lyrical and aesthetically delicate confessions suddenly give way to coarse, cynical images, and a broad spectrum of intertextual cultural allusions.

White Shroud tells the story of Antanas Garšva, a Lithuanian poet and immigrant who has fled the Soviet occupation of his homeland and struggles to make ends meet in his new life in the United States. The work is autobiographical to at least some extent, writes Toivanen.

The narrative itself unfolds on two levels, narrated in two voices: in the New York of the 1950s, in a detached third-person narration; and in first-person excerpts from Garšva’s “notebooks” depicting his life in Lithuania before and during the war. Initially separate, these timelines increasingly bleed into each other as the novel progresses.

Of these layers, the American present of the novel is the more immediately compelling. Garšva works as a lift operator at a luxurious yet sordid New York hotel, mingling with other representatives of the city’s underclass both at work and in his free time, some of them compatriots, most of them immigrants like himself.

The vaguely seedy hotel with its bizarre array of guests – Freemasons, ex-officers of Chiang Kai-Shek, Polish clerics – provides a rich and captivating setting. Within it, the lift itself takes on a heightened symbolic significance in beautiful passages where its rhythmic movements mix with Garšva’s reminiscences of home, dipping in and out of memory, time, the subconscious. There is also a love triangle, although one that doesn’t turn out quite as one might expect. Everything, including passions, take on a faded hue in the characters’ immigrant existence.

By contrast, says Toivanen, the biography unfolding in the sections set in Lithuania is more immediately heavy and cruel in its contents, but Škėma wisely disrupts its rhythm and mixes up its chronology, giving the reader short glimpses of moments rather than the full story.

Škėma’s fundamental interest, he says, is not in the story of the upheavals of the Second World War, but in the act of remembering itself, of trying to find a life worth narrating for oneself. “It is nonsense, of course, to think that my first memory is authentic,” Garšva admits, and that sense of unreliability and instability pervades the novel. He is “searching for a lost world”, but whether that world ever really existed remains an open question.

White Shroud is, in some ways, very much of its time: a story of a (male) writer wandering the streets of an uncaring city, getting increasingly lost in his ruminations on life, art, society and love, all narrated in a somewhat ironic, detached style (“most geniuses were ill,” Garšva muses about his heart condition). The kind of story that high school kids and undergrads the world over yearn for, an artistic ideal.

Existentialism provides the intellectual underpinning: “Sisyphus no longer needs sinewy muscles,” the narrator wryly observes with reference to the ceaseless, pointless up-and-down movement of Garšva’s lift, seemingly a nod to Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus. Among Škėma’s French contemporaries – and rightly or wrongly one always looks to the French for this sort of thing – one might also think of Sartre, or maybe Jean Genet, considering the novel’s focus on and concern for society’s outsiders.

And yet, Toivanen notes, emphasizing such similarities with more famous contemporaries does a disservice to Škėma and the novel, which is also much more than all that and a genuinely unique piece of art. Garšva’s alienation as a struggling immigrant – one among many in the carelessly exploited work force of a teeming metropolis – grounds the work’s more intellectual flights of fancy onto a theme that once again has immediate relevance in the present day.

The narrative is also anchored throughout by the trauma of war and occupation that weighs down on both its timelines. These elements give the novel a heft and realism too often lacking in the more introspective and self-satisfied brands of existentialist prose, make it feel meaningful.

At the same time, that heft also gives Škėma the liberty to take off artistically and to experiment with both language and structure. The fragmentation of perspectives, of time and language itself that define the novel’s tone from its first page to its last are never reduced to the empty trickery of an artist showing off, but instead find meaning as reactions to the immigrant experience and to trauma that are both highly specific and universally human.

The narration frequently unravels into pure stream-of-consciousness and words lose their meanings to become just sounds or rhythms – of a waltz, in the case of the name of Garšva’s lover: E-le-na, repeated again and again. As a poet, Garšva’s experience is also filtered through metatextual layers of cultural references, ranging from high-brow art to a great deal of Lithuanian folklore, but these are organically inserted into the character’s biography and drive the novel’s themes of cultural and temporal displacement.

In Toivanen’s view, Vagabond Voices deserves credit for recently bringing this work out for an international audience, as does the translator Karla Gruodis for rendering it in English – an especially difficult and thankless task as Škėma’s wordplay and layered meanings appear at some points to be almost wholly untranslatable. Gruodis’s rather interventionist style of translation that relies on a heavy complement of footnotes does occasionally pull the reader out of the text, but more importantly it also succeeds in providing a sense of the true complexity of the original without compromising too much on legibility.

White Shroud is not a light book, in either its themes or its style concludes Toivanen. It is, fundamentally, a book about survival. “Everything is because of death,” Garšva explains at one point – everything including his writing, alcohol, the pills for his heart condition. But then, conversely, everything is also because of life: in order to live; to not die.