A coal mining region in Pennsylvania, US, was once known as Little Lithuania. In the 19th century, thousands of Lithuanians came to work in the coal mines, built churches and left six Lithuanian cemeteries here. Today, Lithuanian heritage in Pennsylvania is disappearing.

The town of Shenandoah was once the Lithuanian “capital” in the US. Now, it is a town of dilapidated wooden buildings that has seen its population shrink several times following the decline of the coal industry.

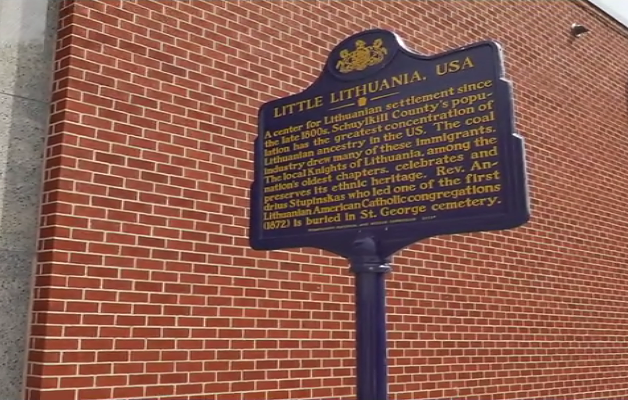

The city’s heyday was in the 1920s when the city’s population was nearly 30,000 people. At the time, Lithuanians were the largest ethnic minority in the city, and several of them were elected mayors. Even today, the Lithuanian surname – Lukašiūnas – can be seen on faded posters in the city, honouring residents who served in the US Army. A memorial has also been erected in the town centre. The sign reads: “Little Lithuania”.

There are still many descendants of Little Lithuania in the vicinity. Alvin Luschas’ grandfather moved to the US from Lithuania in 1905 because he did not want to serve in the Tsar’s army, as Moscow was at war with Japan at the time. The surname comes from the Lithuanian word “lūšis” (lynx). Alvin’s grandfather worked in the mines: “It killed him. He died of coal miners’ asthma. My father worked in the mines too. He was in a disaster – the mine collapsed.”

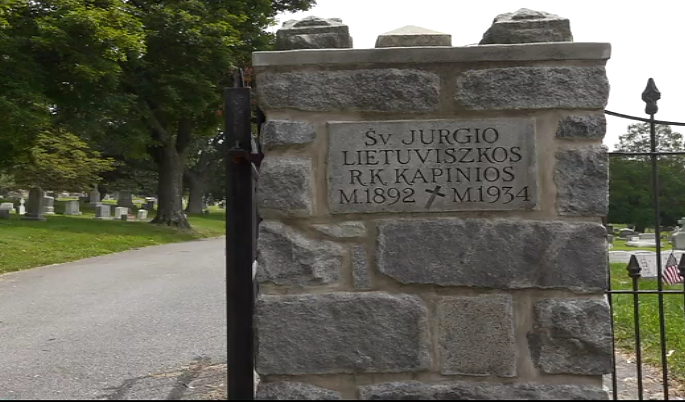

The plight of that generation of immigrants is also reflected in the region’s six Lithuanian cemeteries. “Killed in a mine,” several tombstones of the early twentieth century read. “I feel that my Lithuanian background has created my success in this country. It’s because of the work ethic – there is nothing harder than working in the mines,” Alvinas says.

The grandparents of Eleina Luschas, Alvin’s wife, also moved to the US from Lithuania more than a century ago. Eleina and Alvin met in the Lithuanian primary school. “My mother and aunt often spoke Lithuanian. But we – Alvinas and I – did not learn Lithuanian,” she shares.

“We learned Lithuanian in the first grade of school, we learned the Lithuanian national anthem and a few words, but they wanted to make us Americans. They didn’t want us to know our mother tongue because it was not easy to fit in. […] Oh, how I wish I could speak Lithuanian,” Eleina adds.

The family of Vilius Žalpis also lived in the US for more than a hundred years. He started learning Lithuanian when he was 21. He then also changed his surname from Americanized Zolp back to Žalpis. “I try to learn ten [Lithuanian] words every day. But I always struggle with the pronouns,” he says. Vilius is now the leader of the Šaknys (Roots) project (www.saknys.lt) which aims to preserve Lithuanian heritage in the US and cleans up abandoned Lithuanian cemeteries.

In the neighbouring town of Mahanoy, a former Lithuanian church still bears Lithuanian words on its stained-glass windows. But most Lithuanian heritage here is in a state of decay. “Private property,” is written at the entrance to one abandoned Lithuanian cemetery. “We wanted to come here, but we didn’t get permission,” Vilius says. The company that now owns the site refused to allow the Šaknys project to clean up the century-old Lithuanian cemetery. According to Vilius, it replied that cleaning up the cemetery would only attract more visitors.

According to the locals, the Lithuanian heritage in this region of Pennsylvania is remembered by fewer and fewer descendants. “My husband is half Lithuanian, and I am three-quarters Lithuanian. When things start to blend, people don’t know their origins anymore,” says Eleina Luschas. “I think we have many things to be grateful for – for having the heritage that we have, as well as the opportunity to understand who we are and where we come from,” said Alvin.