Orbis Lituaniae is a collection of nearly 700 stories of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, digitized by the Vytautas Magnus University library in Kaunas. One of these stories is about Gediminas, a famous Lithuanian ruler whose name is as iconic as the castle named after him in Vilnius.

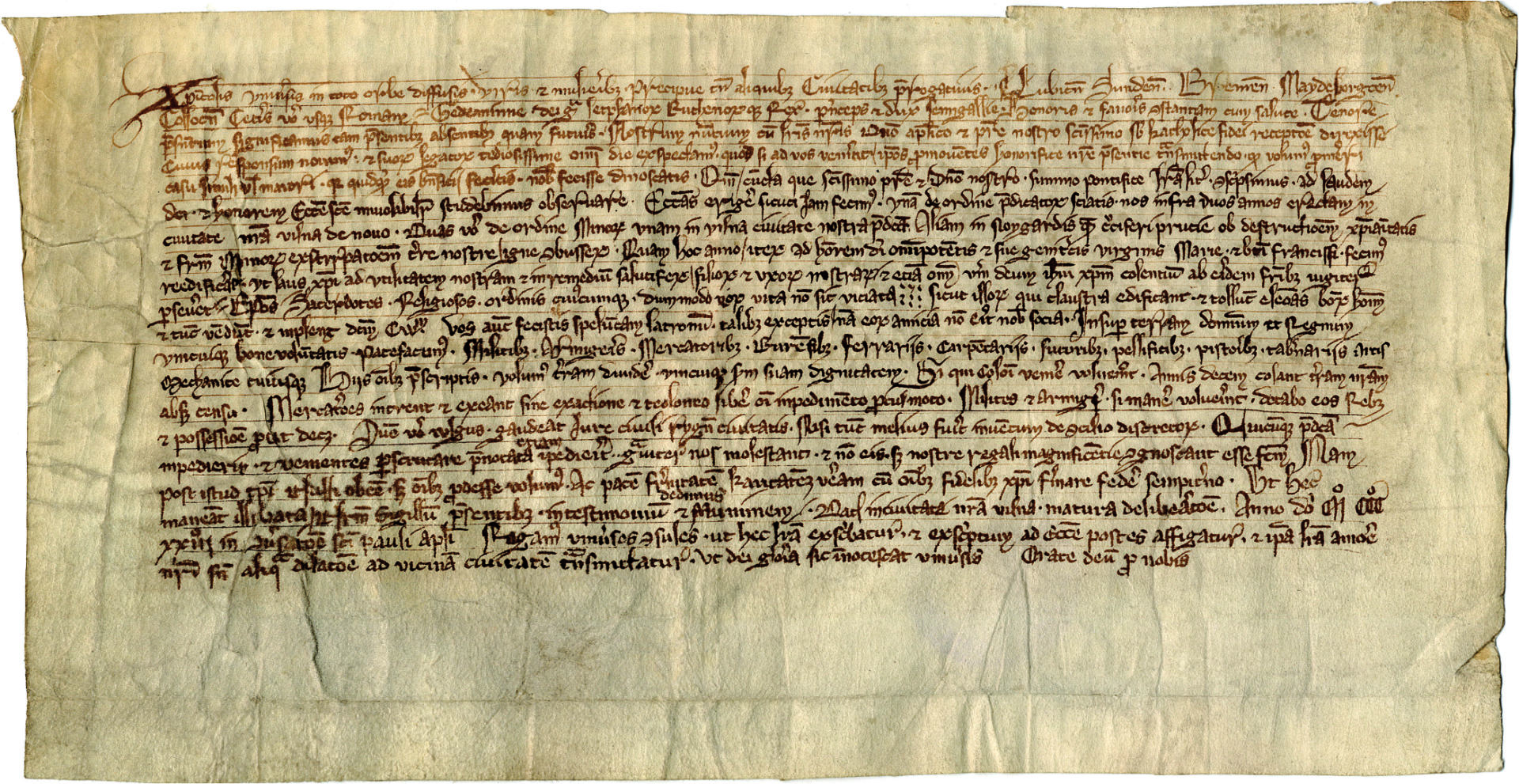

Earlier this year, medieval historian Darius Baronas wrote him, noting that in a feat of medieval diplomacy, Grand Duke Gediminas of Lithuania sent a series of letters to Christian Europe, seeking the pope’s intercession in his wars with Teutonic knights and enticing craftsmen to come to his realm. The famous letters of Gediminas, written in 1322-1323, attracted great interest throughout Europe. Many hoped that Gediminas would at last be baptized and bring Lithuania into the family of Christian nations of Europe.

Earlier this year, medieval historian Darius Baronas wrote him, noting that in a feat of medieval diplomacy, Grand Duke Gediminas of Lithuania sent a series of letters to Christian Europe, seeking the pope’s intercession in his wars with Teutonic knights and enticing craftsmen to come to his realm. The famous letters of Gediminas, written in 1322-1323, attracted great interest throughout Europe. Many hoped that Gediminas would at last be baptized and bring Lithuania into the family of Christian nations of Europe.

In his letters, Gediminas had made some enticing promises: “We open our lands, possessions, and the kingdom to every man of good will: knights, squires, merchants, peasants, blacksmiths, wheelers, shoe-makers, furriers, millers, tavern keepers, and every craftsman. … let [farmers] work the land free of tax for ten years. Let the merchants enter and leave free of tax and customs and without any hindrance. Let the common people enjoy the civil rights of the city of Riga unless, after consulting the learned, we invent something.” Gediminas promised the newcomer farmers when it was time to pay the tithe, they would retain more fruits of their toil than in any other European country. The letters of Gediminas were the first promotional campaign of Lithuania.

Gediminas also promised that, among other things, settlers would be granted the freedom to profess their Christian faith. He also mentioned churches that had already been built for merchants in Vilnius and Navahrudak. He announced that these were ministered by Franciscans who dispose of “complete freedom to baptize, preach, and perform other sacred services”.

Gediminas also promised that, among other things, settlers would be granted the freedom to profess their Christian faith. He also mentioned churches that had already been built for merchants in Vilnius and Navahrudak. He announced that these were ministered by Franciscans who dispose of “complete freedom to baptize, preach, and perform other sacred services”.

On several occasions, he intimated that he was determined to adopt Christianity. In a letter to all Christians, he stated: “We have sent our envoy with our letter to the Apostolic Lord and our Holy Father concerning the acceptance of the Catholic faith. We know his answer and we expect his legates every day impatiently.” More than once, Gediminas noted that he was looking forward to the baptism plan being implemented as soon as possible. Pope John was eventually persuaded that Gediminas did mean what he wrote. He appointed a benedictine monk and the bishop of Alet-les-Bains Bartholomew and the abbot of St. Theofred monastery of the diocese of Annecy Bernard as his legates. They were far from naïve, so in the autumn of 1324, they sent their representatives to Vilnius to assess the situation. Once their agents arrived, they learned from a local Dominican monk, Nicholas, that “the king’s idea has changed so that he does not want to accept the faith of Christ at all.”

During the audience at Gediminas’ court, the legates tried to approach the most important topic gently, but Gediminas soon interrupted them and asked if they really knew what was written in his letters. The messengers replied: “The intention to accept the faith of Christ and be baptised.” Gediminas retorted that he had never asked to write about his baptism and blamed his Franciscan scribe Berthold. He added, “If I ever had such an idea, may the devil baptise me.”

In trying to vindicate himself, Brother Berthold said that he put down only “what came out of the lips of the king: that he wanted to be the son of obedience and surrender to the patronage of the Church, the Holy Mother, and to accept the faith of Christ.” In response, a man from Gediminas’ camp pressed: “So you admit you weren’t told to write about the baptism?” All the Christians argued that being “the son of obedience” and surrendering to the patronage of the “Holy Mother” means nothing else than baptism, yet the Lithuanians were not impressed by such rationalizations. In fact, Lithuania did not accept Christianity until the reign of King Mindaugas,

In trying to vindicate himself, Brother Berthold said that he put down only “what came out of the lips of the king: that he wanted to be the son of obedience and surrender to the patronage of the Church, the Holy Mother, and to accept the faith of Christ.” In response, a man from Gediminas’ camp pressed: “So you admit you weren’t told to write about the baptism?” All the Christians argued that being “the son of obedience” and surrendering to the patronage of the “Holy Mother” means nothing else than baptism, yet the Lithuanians were not impressed by such rationalizations. In fact, Lithuania did not accept Christianity until the reign of King Mindaugas,

The story is part of the Orbis Lituaniae project by Vilnius University.