The Story of a Crucial Document

Lithuania’s primary news outlet LRT.lt posted the little-known story of a short document that had the power to bring the Lithuanian nation to life.

On a winter Saturday in 1918, a little before noon, members of the Council of Lithuania assembled in a flat on Wielka Street. It wasn’t the usual meeting place for the Council of Lithuania established the year before, which normally held its sessions in a building several hundred metres away. But it was a cold day and the host, Dr. Jonas Basanavičius, was saving on firewood. The members gathered in the Sztral House, which also hosted the headquarters of the Lithuanian Society for the Relief of Victims of War, a crucial body for Lithuanian self-rule, to which the Council owed its existence. Sztral House would later become known as the House of Signatories.

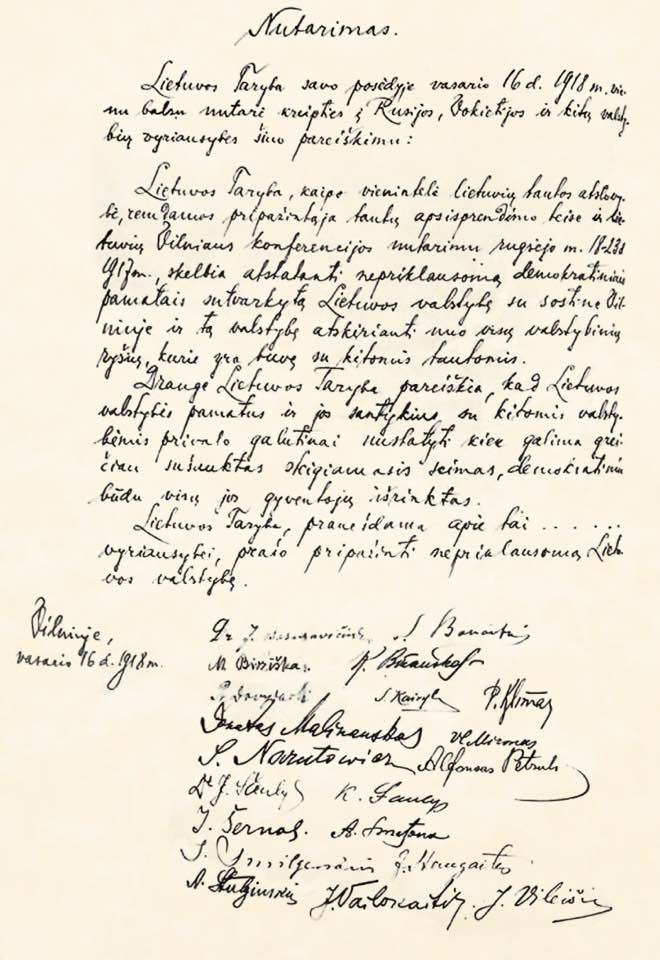

The meeting was chaired by Basanavičius, the eldest of the 20 men. Moving swiftly, they unanimously adopted a short one-page document that had been drafted in advance. Everyone signed in alphabetical order and moved on to other issues on the agenda. Another session was scheduled for the evening and everyone left for lunch, without much euphoria for the crucial judicial step they had just taken.

Since 1795, lands inhabited by ethnic Lithuanians had been ruled by the Russian Empire. As in many places in Europe, the second half of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of a national movement, culminating in demands for some form of autonomy within Russia.

Circumstances changed dramatically with the onset of World War I. Months into the war, the German army marched across Russia, occupying western parts of the empire. For the rest of the war, Lithuania was under German administration.

After the Russian revolution of 1917, Germany considered turning the occupied lands – Mitteleuropa – into a buffer zone of puppet states to contain the spread of the revolution from Russia. The nations of Eastern Europe were to be nominally independent, but tightly controlled by Germany. It was under this plan that the German administration agreed to allow Lithuanians to hold the Vilnius Conference of September 1917, hoping that it would lend legitimacy to an alliance with Germany.

However, the conference adopted a more ambitious resolution, calling for an independent state, and any closer relationship with Germany was to be conditional upon Berlin’s acceptance of Lithuania’s independence. The 214 attendees of the Vilnius Conference also elected a 20-member Council of Lithuania to carry on with the work.

The Council initially tried to balance what was desirable and what was possible. Its first independence act, signed in December 1917, called for “a firm and permanent alliance” with Germany, but Berlin’s reluctance to grant any actual control was exasperating and almost split the Council. It was under these desperate circumstances that the Act of February 16, 1918, was signed. It was addressed to the “governments of Russia, Germany and other states” and declared an independent and democratic state of Lithuania with Vilnius as its capital.

The first order of business for the Council was to publicize the declaration, which the German authorities were intent on suppressing. They seized almost the entire run of the Council’s newspaper, Lietuvos Aidas (Echo of Lithuania), but the Lithuanians managed to smuggle the act out of the country and publish it in German newspapers several days later.

The issue featuring the Independence Declaration was confiscated by the German authorities.

It did not change the situation on the ground, as the country was still under firm German control. It wasn’t until Germany itself had become embroiled in a revolution and was facing certain defeat in the war that the Lithuanians could effectively start building a state of their own, according to the principles set out on February 16, 1918.

The Republic of Lithuania was independent until 1940, democratic until 1926 – but the capital in Vilnius, didn’t materialize until 1939. Algimantas Kasparavičius, a historian with the state-run Lithuanian Institute of History, said the Council probably produced five hand-written copies of the Act: three in Lithuanian, one in German and one in Russian.

One of the signatories, Jurgis Šiaulys, took two copies in German and Lithuanian to Berlin’s diplomats in Kaunas. The Russian copy, along with a Lithuanian one, in all likelihood ended up with the Russian government in Petrograd, according to Kasparavičius, while the last copy must have remained in Lithuania.

This copy was probably handed over to Jonas Basanavičius who chaired the historic Council meeting, according to the diaries of one of the signatories, Petras Klimas. Later, it probably went to President Antanas Smetona’s office in Kaunas, the temporary capital.

In 1940, when the USSR occupied Lithuania, the archives of the president and the Foreign Ministry were taken to Moscow. It’s unclear if the act was among the documents.

Until recently, most people of Lithuania were familiar with a typed version of the 1918 Act of Independence that was reproduced in textbooks and posters. This was not the original document, according to Kasparavičius, but one from 1928 when it was published on the 10-year anniversary of independence.

Until very recently, the hand-written originals were thought to be missing. Many historians had been on a quest to find them and theories proliferated about what may have happened.

According to one, Basanavičius may have put the document inside a book and forgot about it. One of the wilder theories maintained that it was hidden inside a beehive and shredded by bees. Searches were even carried out in a Vilnius townhouse that was owned by Petras Klimas who kept the original act at one point. None of these theories produced any results.

As Lithuania was gearing up for the centenary of the 1918 independence, a business group, MG Baltic, offered a one-million-euro reward for returning the 1918 Act of Independence to Lithuania. The company had been embroiled in a nasty political corruption scandal, so in addition to patriotic fervour, many saw behind the initiative an attempt to redeem its reputation.

In the end, a little-known political scientist from Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas shook the nation in spring 2017 by announcing he had discovered the Act in Berlin. Liudas Mažylis’ quest for the document was as fascinating as it was simple. A history buff, Mažylis later told the media how he decided to spend his holidays looking for Lithuania’s founding document – and Germany’s state archives were a natural place to start.

He emailed Germany’s state archive, stating which period and which topics interested him, a nd was sent a list of files to look at, which he did in two days. He had hoped to find a German translation of the document in the archives of Germany’s Foreign Ministry, so discovering a Lithuanian copy as well was a pleasant surprise.

The discovery sent patriotic shivers up many spines, while the rest wondered whether MG Baltic would live up to its million-euro promise. Mažylis confirmed that he wasn’t in it for the reward, while the company pointed out the condition was returning the Act of Independence to Lithuania. Germany would not give away documents from its archive and only agreed to lend it to Lithuania for five years.

MG Baltic used the money it pledged for the discovery to set up a foundation for historical research, while Mažylis became a household name. He would host a TV programme and published a fictionalized account of his quest for Lithuania’s Act of Independence. In 2019, he successfully ran for the European Parliament with the conservative Homeland Union party.

Meanwhile, the Act of Independence is currently exhibited in the House of Signatories in Vilnius, in the same room where it was signed by 20 men 102 years ago.