Changing my name does not mean I’m betraying my identity

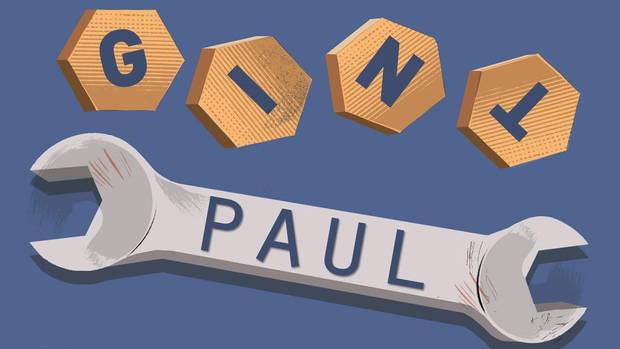

G. Paul Šileika (Contributed to The Globe and Mail, Originally published Jan 20th, 2014)

‘That’s an interesting name. Where is it from? Is it short for something? Europe, eh? Were you born there?”

Before I can even begin to build a rapport with someone or connect on a common interest, my name catches his or her attention. Before I can share my personal story one is already written for me.

My parents named me Gintaras and called me Gint for short. If you read that as Jintaras and Jint then you, like the rest of the world, have mispronounced my Lithuanian name. That consonant is a hard “g” like gramophone, not soft like gin. While my grandparents immigrated to Canada more than a half-century ago, Lithuanians are a proud people and often maintain their identity for many generations. This includes sometimes giving your children names that are impossible to anglicize so that everyone can ask where you’re from.

My mother explained to me that in the 1970s multiculturalism was on the rise and it became commonplace to give your children foreign names that reflected their ancestral origins. I can appreciate that sentiment since I value diversity and multiculturalism, but there can be a middle ground. For example, Lucas and Thomas in Lithuanian are Lukas and Tomas. The direct translation of Gintaras is “amber,” which anglophones see as a girl’s name, adding to the peculiarity of my identity.

While my friends and family who have known me for years argue that my name is easy to pronounce, most new people I meet still struggle it. For many years I had to create a way for people to remember the correct pronunciation: “It’s Gint. Like ‘mint’ with a G.”

…CONTINUED …Read the rest of this entry at The Globe and Mail.