By Otis Tamašauskas

A story of two remarkable people, whose lives were culturally significant but were largely undiscovered in their community.

“The most we can do is look more closely”

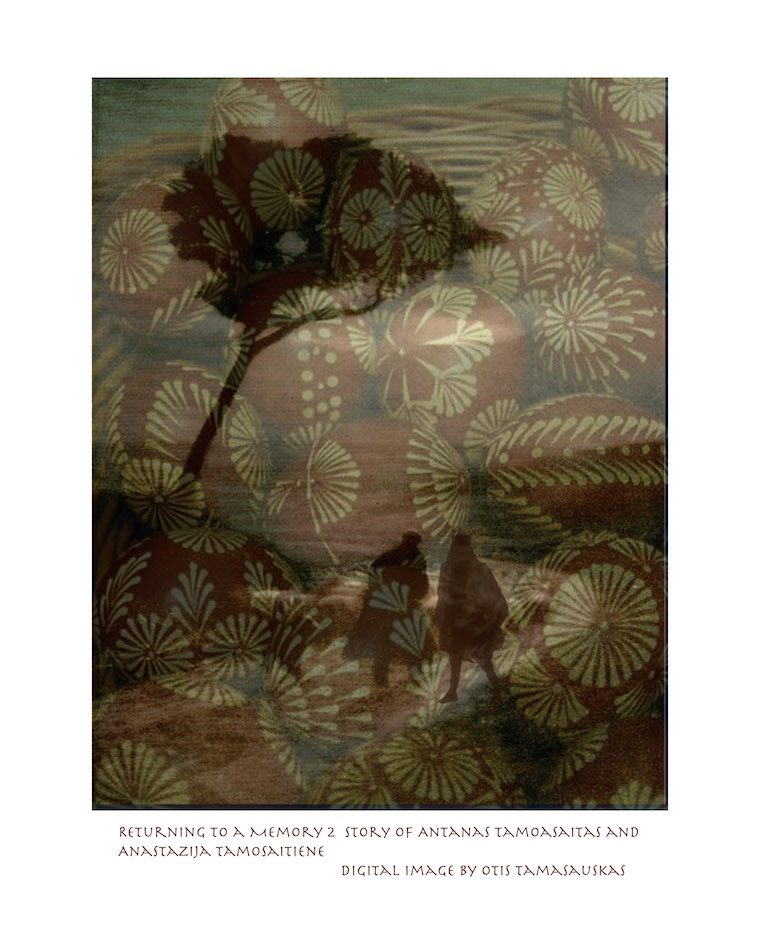

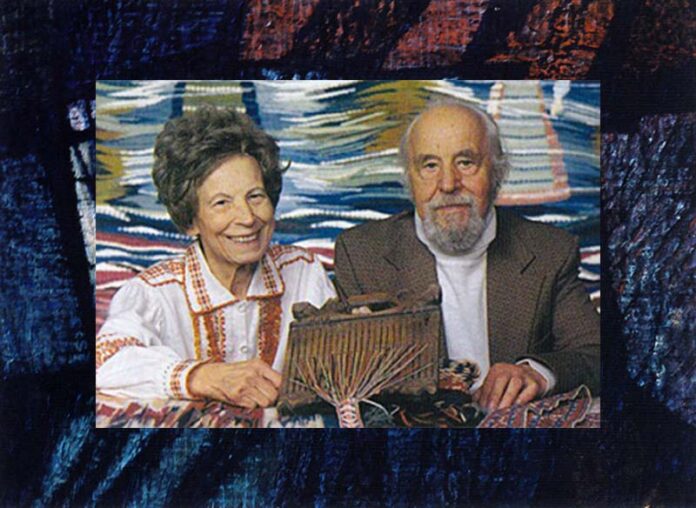

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Windsor I came across an exhibition by a Lithuanian Canadian artist named Antanas Tamosaitis (1906 – 2005). Being of Lithuanian descent myself, as well as an artist, I was curious about his textile weaving, painting and printmaking. Seeing Lithuanian-influenced cultural art was not an everyday occurrence in Canada. In my senior year, I discovered more about this Antanas Tamosaitis. He was married to a renowned weaver named Anastazija Tamosaitiene (1910 – 1991), (In Lithuanian culture surnames have specific masculine and feminine forms. The masculine name ends in -as, -ys,- or -is, it’s feminine equivalent ends in – iene for married women). Anastazija was credited as a major influence in Lithuanian traditional textile arts and her weaving was second to none. She was commissioned by the British-Lithuanian Association, to weave a wedding gown for Princess Diana in the English wedding of the century. Rumour has it that she even has a weaving hung in the Vatican. Many honours and awards followed.

In interwar Lithuania the two were equivalent to modern day ethnographers and folklorists. They passionately foraged through rural Lithuanian towns and villages, with a personal and aesthetic view, collecting, documenting and saving traditional folk designs of art and textiles. They recorded a way of life that was fragile and disappearing. My view is that they did not simply record folklore, but actually helped preserve and reintroduce aspects of the cultural identity of Lithuania through the practice of art.

“Identify beauty”

Their combined efforts resulted in a historically important series of 8 books about Lithuanian village art. Their book, “Lithuanian Women’s National Costumes” (1939), established a foundation for further study and recovery of the national costume and traditional folk attire.

Many of Antanas and Anastazija’s weavings and tapestries, were recognized for their creative excellence. Antanas was given the highest awards at the World Exhibition in Paris 1937, Berlin 1938 and New York City 1939.

The couple lived vital and effectual lives.

Antanas taught at the Vilnius Art Academy, and then headed the textile arts department at the Kaunas School of Applied Arts. Anastazija taught weaving at the Chamber of Agriculture’s Folk Art Department at Dotnuva, then, from 1940 to 1942, she taught textile arts at the Kaunas School of Applied Arts.

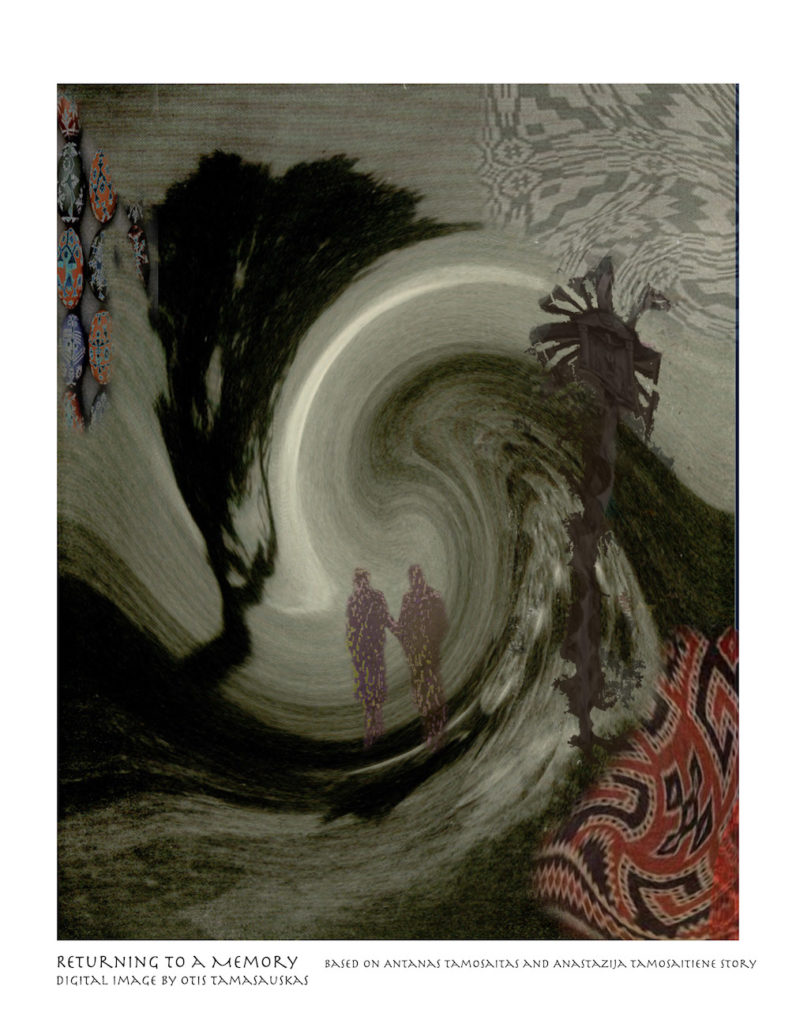

“The eye exists in a savage state”

With the onslaught of World War 2 came fears of Soviet occupation and repression. Antanas and Anastazija understood that their lives were undergoing a turbulent change. With no time to spare, they carefully packed trunks full of their folk-art collections and important design books and fled Lithuania. Arriving in Austria in 1945, they opened an art studio for other Lithuanian refugees. From 1946 to 1948 they both worked in Freiburg, Germany, where they both became instructors of weaving and textiles at, the Ecole des Arts et Métiers de Freiburg.

“A Reflection”

Because of the imposing Soviet regime, Antanas and Anastazija could not return to Lithuania. With a new sense of creative purpose, they immigrated to Canada.

“There was steadiness in their passion”

Though the Tamosaitises lives were drastically changed, the quality and solvency of their artistic practice remained unaltered.

They spent two years living in Montreal establishing a Studio of Weaving and National Costume. In 1949 Antanas became the Director of the Art and Craft Academy at the YMCA in Montreal.

In 1950 they established their home and studio outside of Kingston, Ontario. Here they dedicated their lives to the pursuit of art and the preservation of Lithuanian folk culture.

Their home became a museum for textile arts and people from all over North America came to see their work. Finally, in 1989 they moved to Gananoque, Ontario.

In 1990 I was featured in an exhibition alongside some of Anastazija’s tapestries in Toronto. While installing the exhibition I had the opportunity to speak with her. I told her that I taught fine art at Queen’s University, in Kingston, and to my delight, she invited me to visit her in Gananoque for tea. Unfortunately, before I was able to take her up on her offer, she passed away, roughly around the time that Lithuania gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

“Possibilities”

In 1998 my wife and I moved to Gananoque, from Kingston. My oldest son, Kaz, came home from Gananoque Secondary School one day and mentioned that he noticed an unusual older person collecting junk (though for an artist, perhaps a more suitable term is “objects of interest”). This man lived in an old coach house on the edge of Oak Alley off of King Street. The story resonated with me, as it reminded me of my own practice of collecting curious objects to employ in my art. I then realized that Kaz was speaking about an elderly Antanas Tamosaitis, now in his late 80’s. Unfortunately, I made no attempt to meet him: something I regret to this day.

Intriguingly, a few years before we moved to Gananoque, I was contacted by Peter Regina, a builder, who had aspirations of establishing a Lithuanian Cultural Museum on Chisamore Point Rd in Gananoque. The building was made, but the finer finishing elements were still in progress. Peter asked me to design the gates to the museum. I drew up plans, but he felt they were unrealistic and would create some issues with fabrication. He also went to the length of flying in experienced craftsmen from Lithuania, to help with the final touches. They build two unique Lithuanian wooden crosses. One of the crosses was erected in the Gananoque sculpture park but is now mysteriously missing. The other cross is in a field off to the south of the 401 Highway, approximately 200 yards outside of Gananoque, heading east.

As I think back to all of these connections, the conditions necessary for a Lithuanian Folk Art Museum in Gananoque were favourable. Antanas and Anastazija collected hundreds of culturally significant artifacts and brought them to Canada. Their trunks of weavings, textiles and design books were right here in Gananoque. The news that the Iron Curtain fell in 1991, however, changed everything. The museum would not be sustained with the Tamosaitis collection as the Lithuanian Government embraced Antanas with open arms and flew him back to Lithuania with all the treasure and artifacts. He was made a lifetime honorary professor at the Vilnius Art Academy. Gananoque’s (and Canada’s) affair with two of Lithuania’s most important cultural and artistic figures was over. He passed away in Vilnius in 2005 at the age of 99.

In 2019 I visited Vilnius with my family. The city is a stunning mixture of medieval and baroque architecture with endless narrow cobbled streets—a visually and culturally engaging place. While walking these streets in the most prominent part of the Old Town, in disbelief, we stumbled upon a Museum dedicated to Antanas and Anastazija Tamosaitis. The realization of the significance of a story spanning decades, continents, and political regimes, struck me. What doesn’t cease to amaze me about all of this is that little Gananoque has a profound connection with the historical and cultural identity of Lithuania. Two giants of Lithuanian culture and art lived amongst us, and their prolonged dedication throughout their extended refuge from Soviet repression is now celebrated and recognized as having protected many vital forms of Lithuanian folklore and cultural history.