On July 6, Lithuania celebrated State Day, commemorating the coronation of the nation’s first and only King Mindaugas in 1253. Little is known about the ceremony, least of all its exact date.

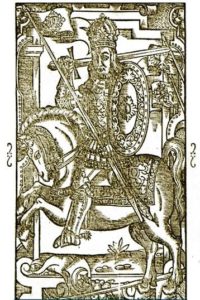

Mindaugas was a medieval warlord who succeeded in uniting local fiefdoms under his rule in 1236, laying the foundations for the Lithuanian state. Few details are known about his coronation as the first Lithuanian king, except that he did receive a crown from Pope Innocent IV.

Historian Rimvydas Petrauskas of Vilnius University told LRT.lt that there is no doubt about the fact of the coronation, because there is the pope’s document, permitting Mindaugas to be crowned, setting out the procedure, and even identifying the people to conduct it. However, a unique source, discovered a few decades ago, conventionally called Description of the World, includes the coronation of Mindaugas. The coronation is also attested to in the chronicles of the Livonian Order. But there is not much detail, not even where the ceremony took place, says Petrauskas, and “the biggest fiction in the Lithuanian history is the date”.

It is fairly certain that the ceremony took place on a Sunday in July. However, when Lithuanian leaders decided to make the coronation of Mindaugas a national holiday in 1990, history professor Edvardas Gudavičius was entrusted with studying the matter and identifying the most likely date. He suggested July 6, which has been a public holiday since 1991.

In order to receive a crown from the Pope of Rome, Mindaugas had accepted Christianity in 1251, although the majority of his subjects remained pagan. There has been much speculation as to how sincerely he embraced the new faith, or whether he was just a Christian by necessity.

According to Petrauskas, becoming a Christian king was a way for Mindaugas to win recognition for himself and his kingdom. It was essentially an affirmation of his sovereignty in that part of Europe.

The pope’s recognition meant that other Christian entities, such as the German Livonian Order, could not legitimately attack it, which was a pressing issue at the time. Kingship also established Mindaugas’ authority among local Lithuanian dukes. His primary motivation of Mindaugas was pragmatic – he needed to strengthen his rule, which was very weak. “He was the first ruler who united Lithuanian lands, the first monarch,” says Petrauskas.

Apparently, the crown was not enough – Mindaugas and his two sons were assassinated by a rival a decade later, in 1263. Even before his death, Mindaugas is was accused of abandoning Christianity and reverting back to pagan faith. However, Petrauskas cautions against accepting this as fact, since the only source is the Livonian Order. After a brief truce, the military conflict between the German knights and the Lithuanians resumed. The Germans interpreted it as evidence of Mindaugas’ abandonment of Christianity. According to Petrauskas, it was not necessarily so. The Livonian Order gave an interpretation favourable to themselves, in order to justify their actions.

After Mindaugas’ assassination, his kingdom disappeared, but the Lithuanian state persisted. Subsequent rulers pondered becoming kings, as well, most notably Grand Duke Vytautas in the 15th century. However, Mindaugas remained the only Lithuanian king, even though Lithuania came close to crowning Mindaugas II in the 20th century.

The Council of Lithuania, which declared the country’s independence in February 1918, initially considered making it a constitutional monarchy. On July 11, 1918, the Council invited Wilhelm von Urach, a German prince, to become King Mindaugas II of Lithuania. However, due to opposition both in Lithuania and Germany, the invitation was rescinded the following November. Apparently, Wilhelm von Urach was dubbed the one-hundred-day king.

News from LRT.lt