In an interview on the Polish radio station Znad Wilii last week, Lithuanian Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė said that Lithuania’s society is poisoned by Russian culture because it was over-emphasized during the Soviet era. Asked about the recent initiative to ban Russian authors’ works in Lithuania, she said: “I think we have [a] certain intoxication with Russian culture in our society. I am not surprised by the reluctance to stage, listen, read or do anything else with it now.”

During the period of Soviet occupation, Lithuania’s society was “fed with Russian culture” as the myth was being created that this culture was “somehow very, very great”, which is why even now a part of the society tends to put it on a pedestal. “Russian culture has clearly dominated the repertoires of our theaters, and elsewhere, and it seems to me that we have had this historical circumstance for a very long time mainly because we have talked little about other cultures, such as the Polish culture, the Swedish culture, the Ukrainian culture, the Spanish culture,” the Lithuanian prime minister said.

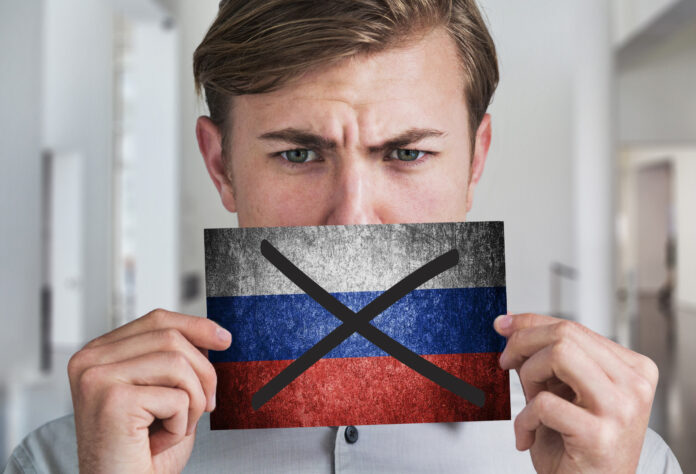

Last April, in response to the massacre of civilians by Russian troops in Ukraine, the Lithuanian Art Creators’ Association called for an embargo on Russian culture and art in Lithuania until the end of the war in Ukraine. Several Lithuanian theatres have already announced their decision to remove works by Russian authors from their repertoires.

In the Lithuanian cultural magazine “Šiaurės Atėnai” (Athens of the North), Audrius Sabūnas recently wrote about another aspect of Russian culture that Lithuanians should give up.

Russia’s war against the proud nation of Ukraine has provoked an extreme wave of cancel-culture, which is resonating deeply with Lithuanians. Lithuania is remembering historical injustices and raising questions of redress and perhaps even revenge in the form of protests against monuments to collaborators and others, going as far as demanding the boycott of Russian language and literature.

Although there may be differences of opinion among Lithuanians regarding Russia itself or the Soviet era, most would agree that Russian oppression for the majority of the past two centuries resulted in more bad than good. It may be difficult to list all the negative aspects of bearing that yoke, the author states, but the purpose of his article is to review one of them – which may seem insignificant, but it is one which Lithuanians encounter almost every day, and it is undeniably “a product of Russian occupation of our territory and our consciousness.” It is time to uproot it from our lives, he suggests.

Sabūnas says that as a Lithuanian who knows Russian fairly well, he notices that widespread use of Russian swearwords has not abated, and for many they have become an intrinsic speech habit in Lithuanian. He remembers swearing as a teenager, to fit in, because it was manly, even a rule – causing rejection if it wasn’t followed. He contends that although it hasn’t changed radically in Lithuania, peer pressure of that type is lessening today.

Allowing that swearing is excused as being a natural way to “let off steam”, the author poses some vital questions: why do Lithuanian speakers still need to use Russian swearwords, a holdover from as far back as Czarist times? And why are they still used in Lithuanian films and even by politicians? Can we not find Lithuanian equivalents or, better yet, learn more subtle ways of asking for attention or expressing emotions?

Understandably, the Russian war on Ukraine and its effect on the economy has increased the level of agression in our society and does make one want to swear. But that’s no reason to swear in Russian. On the contrary – isn’t it incongruous to despise the dregs of Russian culture and yet use their vocabulary? We have plenty of swearwords in Lithuanian, with an intricate grammar that allows boundless variations. It’s time to send back the daggers that carried in this unwelcome feature of our spoken word.